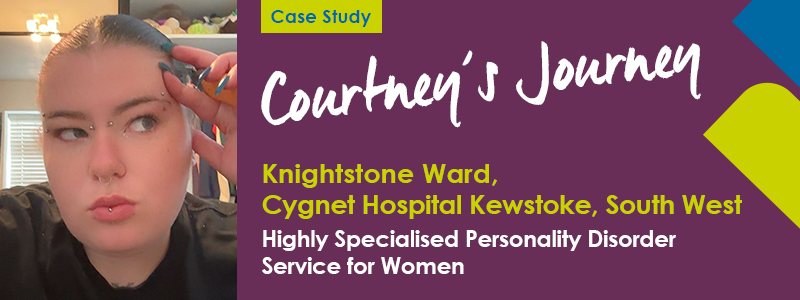

Courtney’s history

Reflecting on her upbringing, Courtney’s said it, “…wasn’t the best.” She was adopted early in life, and her abiding memory is one of being treated differently from the other children in the home. She was subject to physical abuse that went on throughout her childhood.

Aged 11, Courtney was made to feel she was too big and began to restrict her eating. As a teenager already experiencing bullying at school, when self-harm became apparent at home, she was locked in her room.

Courtney sought mental health support, but quickly lost confidence in sharing her thoughts and feelings. Things she said in private were shared with her family, which only worsened her mental state and willingness to open up.

The next three years included overdoses and detentions under the Mental Health Act, culminating in a jump from height that shattered Courtney’s lower limbs, neck and back. She remembers the experience of care from police and paramedics who revived her as the first time she had felt looked after.

After almost a year in a wheelchair, Courtney moved out of her childhood home. She spent time between supported living and the hospital, believing she would never get better.

When Courtney came to us

Courtney was scared about her admission to Knightstone Ward at Cygnet Hospital Kewstoke, why she was there. Wondering why she was here at all had been a persistent preoccupation since regaining consciousness after her fall.

She had more and more debilitating flashbacks. She couldn’t put these experiences into words, just like she couldn’t describe her other feelings. They key information received by the team on Knightstone Ward was that Courtney had difficulty in emotional regulation and managing negative intrusive thoughts, her response to which led her to put herself in danger.

Courtney’s care

On admission, Courtney was assigned staff to work with her on a 2-to-1 basis. She proved willing to engage in treatment, despite struggling to find words for her feelings, and quickly progressed to having one, and then zero, additional care staff assigned to manage the risk of self-harm.

Although talking about her life was a new experience, she appeared to relish the chance to be heard. Intense moods and self-destructive urges still overwhelmed her at times, but she appreciated the boundaries and the time staff took with her to explain things. She recalls them, for example, explaining the limits of their relationships, whilst also connecting with her and validating her experiences. It was the first time, she says, she felt part of a group, with genuine connections.

Joshua Yeates, Psychologist on Knightstone Ward said “There was a striking shift in Courtney’s mindset during her stay. I recall how incredibly dark things were for her when she arrived, as if she had no sense of a future. She’d always been seen as a problem by people around her; at one point, even a psychiatrist had said “This is never going to change, you’re a revolving door patient”.

“We thought together about the impact that would have had on her, how she might have internalised this idea. A big part of the work we did was reframing – instead of seeing herself as inherently problematic, we thought about the context of her behaviour and others’ reaction to it; maybe how Courtney was now was the reasonable upshot of her life history.

“The problem was not her, but that people didn’t know how to deal with her or help her. We tried to move away from just thinking about her problems, and made room instead for her strengths. By the time Courtney left all she could think about was her future and getting on with her life.”

Courtney was a quick learner – she enjoyed practicing being assertive and found it a revelation that she didn’t have to say sorry but could express her wants and needs. Another revelation was understanding that others may have had similar experiences, something she wouldn’t have known had they not felt it was safe to talk.

Josh commented, “Courtney was really artistic and one thing that I think worked well was harnessing her talent for creativity. On leaving she created an amazing booklet, a handbook for herself detailing some of the skills and coping techniques she’d learnt, reasons to keep going, pictures of happy memories, peer testimonials, that sort of thing. I don’t think she saw herself as likeable before, but by end she was just this bundle of creativity, much more confident and so popular with her peers and the staff.”

She came to realise and value that she was not unique in her feelings, and that sharing experience could create a sense of solidarity. She says, “you could speak your problems there and not be judged for it.”

Whilst At Cygnet Hospital Kewstoke, Courtney was assessed for Autism. Once diagnosed, and having others accept this as just another facet of uniqueness, she began to recognise how much her autism “was part of why I am like I am.”

Reflecting on the diagnosis, Josh said “It wasn’t obvious that Courtney had Autism as she’d learnt to mask, but we came to recognise the extent to which she would get overwhelmed on a sensory level and shut down. One of the things we did well with Courtney is figure out and recognise experiences in the here and now, and respond to them.

“Once, I recall when she got overwhelmed, we stopped talking and instead drew pictures together to convey what we were feeling in the moment. It meant she didn’t have to shut down and could find ways to communicate instead.”

Courtney today

Eighteen months following her admission to Knightstone Ward and Courtney is back in the community in a supported living complex, sharing a flat with other young people. Courtney is confident these days that, however tough it feels, things do get better.

Since being discharged, she can list a number of accomplishments – she has been able to assert herself with healthcare staff and advocate for medication changes that suit her. She has applied to go back to college and is waiting for a place on a foundation course in paramedic science.

Courtney is keeping on top of her activities of daily living without pushing herself too hard. She uses the ‘Stop’ skill and mindfulness technique she learnt in hospital to ground herself, particularly at night when self-destructive temptations are strongest. If she has flashback of her jump, she knows what self-soothing techniques work best for her.

Courtney still feels she is not going to be heard some of the time, but she knows herself better, and challenges herself not to assume no one will ever believe her. Her assertiveness skills, she says, help her negotiate all that, and have helped her enlist the help of her Care Coordinator to find a supported living set-up with four others who have grown close through their journeys through hospital.

“I’m still trying to find myself, still struggle often to recognise what I’m feeling, but what I can say is I’m enjoying my life now. I mean, I have good days and bad days, but I’ve got strategies ingrained from my time at Kewstoke – I can stop and think. I’ve learnt to cope with myself and fight for myself. I’ve got friends. I can be the hope for others and I’ve got a reason to wake up every day.”Courtney